The Other Side of The Coin: Digital Cameras Used to Back the Police’s Side of The Story

Image courtesy of http://www.npr.org/2011/11/07/142016109/smile-youre-on-cop-camera

Over the last year or so, we’ve seen a tremendous amount of social activism that is supported through people’s use of social media, particularly on their cell phones. The Arab Spring is a particularly good example of this, as well as the labor protests in Spain and other parts of Europe. In these instances, individuals have taken advantage of texting, Twitter, and Facebook to coordinate public protests, while others have used mobile devices to take photos and video footage of events. These materials are then posted to a variety of social media forums and are often taken up by news agencies and human rights organizations to draw awareness to events. In this way, individual citizens are witnessing events and creating information that often calls attention to abuses and violence against people seeking to defend or garner human rights for themselves.

Given all of the stir that this sort of citizen witnessing is causing, and the fact that the images and videos collected from cell phones can be used as evidence against individuals, public agencies (such as police forces), or even governments, it isn’t too surprising that these same groups are getting savvy and beginning to collect their own digital documentation to as potential evidence defending certain actions. As a story aired on NPR on November 7, 2011 demonstrates, this is exactly what is happening in Oakland, CA as well as smaller towns in the US:

The next time you talk to a police officer, you might find yourself staring into a lens. Companies such as Taser and Vievu are making small, durable cameras designed to be worn on police officer’s uniforms. The idea is to capture video from the officer’s point of view, for use as evidence against suspects, as well as to help monitor officers’ behavior toward the public.

As stated in the article, police departments feel that all to often, they have no hard evidence to back up their side of cases investigating officers for wrong-doing. These cameras would allow them to gather such material. However, the cameras also raise other human rights related issues, such as questions about unauthorized surveillance or invasion of privacy.

Cameras Everywhere: A Report by WITNESS

Grace Lile, the archivist for WITNESS, a video-for-change advocacy group located in Brooklyn, NY, forwarded me information on the report described below. While the report paints a picture of the current uses and further potentials for video in advocacy, Ms. Lile tells me that it does not thoroughly treat issues related to archiving and preserving the footage captured for advocacy campaigns. She has asked me to post about the report with the hope that readers will generate discussion related to archiving human rights video materials. So, I encourage you to read the report and post you comments or insights here. ~Sarah

Cameras Everywhere

Image courtesy of http://www.witness.org

WITNESSrecently published a new report, Cameras Everywhere: Current Challenges and Opportunities at the Intersection of Human Rights, Video and Technology (available here) concerning the importance of video in contemporary human rights activism. As stated in a press release, the report “provides a roadmap… on how to create a more powerful video-for-change revolution.”

Launching [September 6, 2011], the Cameras Everywhere report calls on technology companies, investors, policymakers and civil society to work together in strengthening the practical and policy environments, as well as the information and communication technologies, used to defend human rights.

“Today, technology is enabling the public, especially young people, to become human rights activists, and with that come incredible opportunities. Activists, developers, technology companies and social media platforms are beginning to realize the potential of video to bring about change, but a more supportive ecosystem is urgently needed. It is our duty, through this ecosystem, to empower and protect those who are risking their lives,” said musician and advocate Peter Gabriel, co-founder of WITNESS.

The report draws from the expertise of 40 experts in technology and human rights to paint a picture of the current role of video in activism, as well as to make recommendations for how to further mobilize individuals to take advantage of this powerful medium as they witness key events. Based on interviews with these 40 experts, the report presents the following key findings:

- Video is increasingly central to human rights work and campaigning. With more human rights video being captured and shared by more people than ever before–often in real-time and using non-secure mobile and networked tools– new skills and systems are needed to optimize lasting human rights impact.

- Technology providers are increasingly intermediaries for human rights activism. They should take a more proactive role in ensuring their tools are secure and integrating human rights concerns into their content and user policies.

- Retaliation against human rights defenders caught on camera is a commonplace, yet it is alarming how little discussion there is about visual privacy. Everyone is discussing and designing for privacy of personal data, but the ability to control one’s personal image is neglected. The human rights community’s long-standing focus on anonymity as an enabler of free expression must now develop a new dimension–the right to visual anonymity.

- New vulnerabilities are emerging due to advanced technologies, like facial recognition, which are often instant, global, networked and beyond the control of any individual.

- With more videos coming directly from a wider range of sources, we must also find ways to rapidly verify such information, to aggregate it in clear and compelling ways and to preserve it for future use.

- Ethical frameworks and guidelines for online content are in their infancy and do not yet explicitly reflect or incorporate human rights standards.

- Neither the United States nor the European Union routinely applies human rights standards in forming internet policies. And intergovernmental organizations, such as the UN, are not yet agile players within the policymaking arena of the internet. Meanwhile some governments, notably China, are making headway in both shaping policy against domestic freedom of expression and seeking to influence international standards.

Phones Powerful Human Rights Tools Only When Companies Don’t Side with Repression

On August 9, 2011, Katrin Verclas posted a piece at MobileActive.org demonstrating the obverse of power of cell phones as a tool for citizen journalism and human rights activism. As much as we laud the power of mobile technology for helping to call immediate attention to human rights situations around the world, it is sobering to remember that the companies that make it possible for people to communicate and share information via cell phones can be the single largest obstacle to using our phones as powerful tools of protest and awareness-building. As Ms Verclas reports, mobile phone companies side more often than we would like with the repressive regimes that people–their customers–seek to resist:

Vodafone’s recent decision to shut down its communications network in Egypt and the delivery of pro-government propaganda via text message over its network made the news but that was just the tip of the iceberg. The examples abound: Uganda operators monitored and blocked certain SMS keywords in the advent of the recent election there, pro-Zanu propaganda is widely delivered over Zimbabwean operator networks, Russian mobile operators agreed to ‘police’ the Internet and their networks at the behest of the Russian government, and Belarussian telcos routinely supply information to the security police, including location information of known political activists.

This close collaboration of many operators with repressive states has been going on for some time but there is now a new activist movement forming, holding telcos accountable and to a higher standard. Led by activist shareholders and advocacy organizations like Access, activists point out that the negative publicity of this corporate behavior carries financial implications that pose a risk to telco investors.

Ms. Verclas goes on to illustrate how activist groups such as Access Now seek pressure telecommunications companies to stop siding with repressive regimes, namely, by pressuring them through bringing liability suits for injuries incurred and lives lost in areas of repressive conflict that could have been prevented if victims had had cell phone service. The goal of Access Now is to pressure telecom groups to live up to five principles, which are as follows:

- Providers should retain complete control over their network at all times and ensure

that users always have access to it. - Providers have a duty to protect their users.

- Providers should uphold principles of non-discrimination and should abstain from filtering their networks, except for the purposes of network security and management.

- Providers should uphold principles of transparency, accountability, appealability, and due process in all of their actions and transactions.

- Providers should commit to using spectrum allocation in a judicious and equitable manner.

Activists are using lawsuits as a means of putting moral and financial pressure on telecommunications companies to avoid implicitly siding with repression, which is what they in effect do when they think of their bottom lines before the lives of the individuals who use their service.

Video Witnessing in Syria

Image courtesy of The New York Times http://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/19/world/middleeast/19syria.html?pagewanted=1&_r=2&nl=todaysheadlines&emc=tha22

Liam Stack’s June 18, 2011 New York Times article, “Activists Using Video to Bear Witness in Syria” describes Syrian activists’ efforts to draw attention to a three-month-old popular uprising that is getting little accurate press coverage. As described in the article, Syrian media is not covering events accurately, while foreign media representatives are barred from entering the country to report on events. The solution that the activists have hit upon is to upload video footage to YouTube and Facebook whenever possible–a difficult feat given the rolling internet blackouts that the country is experiencing as the government tries to quash electronic communication about the rebellion against the Assad family, which has ruled Syria for 40 years.

Like the other events of the Arab Spring, digital communication is proving to be an important tool for Syrians trying to gain freedom from widespread illegal acts carried out by their government. Social media serves a fundamental role in circumventing the government’s heavy-handed attempts at silencing protest, as well as accurate coverage of events there. As stated in Stack’s article:

The operation here, which started in March, has grown in importance in the last two weeks, since Syrian forces moved into the [Turkish border] region with tanks, artillery and helicopter gunships. By this weekend [June 18, 2011], the activists had loaded more than 250 videos onto their YouTube channel, Freedom4566, which have been viewed more than 220,000 times.

Hiding behind shuttered windows, down dark alleys or on hilltops high above besieged towns, the activists shoot video of the security forces as they push the violent crackdown across Syria’s rural northwest. The men (none of the activists in the media center are women) upload their videos to social media sites like Facebook and YouTube, which Mr. Saeb praises as “the most realistic.”

The material the present reflects that:

Their cameras captured armored trucks whizzing through the streets and fires burning the valley’s slender evergreens, which they said were set ablaze by the army. By afternoon the smoke could also be seen from the tent city below the media center.

The hope of the “cyberactivists” (as they are referred to in the article) is that posting the videos of events they have witnessed to popular social media sites will draw the world’s attention to what is happening in Syria.

Verifying Social Media Content: The BBC Approach

One of the challenges faced in digital activism is knowing whether or not digitally-generated documentation of abuses is valid. Materials circulated via social media can be particularly tricky because content can be lifted from other sources or doctored. Thus, organizations that wish to maintain a reputation of presenting accurate information need to invest significant time in determining that the digital materials they post is accurate–a process known as “fact checking” in the field of journalism.

BBC’s method for verifying social media

“#bbcsms: BBC processes for verifying social media content“, an article published by Alex Murray on the BBC College of Journalism Blog details the process that the newsroom in London engages in as reporters cover the events of the “Arab Spring.” As stated on the blog, some of the methods engaged for verifying social media content for accuracy and veracity include the following:

At the UGC (user-generated content) Hub in the BBC Newsroom in London, our process has become much more forensic in nature and includes:

– Referencing locations against maps and existing images from, in particular, geo-located ones.

– Working with our colleagues in BBC Arabic and BBC Monitoring to ascertain that accents and language are correct for the location.

– Searching for the original source of the upload/sequences as an indicator of date.

– Examining weather reports and shadows to confirm that the conditions shown fit with the claimed date and time.

– Maintaining lists of previously verified material to act as reference for colleagues covering the stories.

– Checking weaponry, vehicles and licence plates against those known for the given country.

The article further notes that this is not the full extent of their activities; rather, it is a list of their most common practices. Following these practices, verification can take as little as a few seconds and as long as several hours, but key to their success in reporting these events is that the BBC has an Arabic division with people who can distinguish accents. This allows reporters to determine whether a particular audio or video clip originates in eastern or western Libya, for example. The article also reports that correspondents pay attention to details like shadow length in images to verify the reported time of day, or draw from personal knowledge of locations for determining that a place is accurately reported.

Implications for human rights documentation efforts

Though human rights groups often do not have the same monetary and infrastructural resources that a professional organization the likes of the BBC has, they can rely on several of the steps listed above to help verify content they wish to disseminate for awareness-building and activism. For example, field workers should be able to draw on their familiarity with events and locations to verify that video or photograhic material indeed represents these places and events. Grassroots groups can also draw on their own knowledge of local linguistic differences to confirm that speakers’ accents or colloquialisms captured in footage are typical of the area where an event is reported to have happened.

A further implication of adopting some or all of the steps outlined in Mr. Murray’s blog post is that doing so will allow groups to attach important metadata to digital items so that they can potentially serve as evidence in legal cases or as part of memory and advocacy building projects. Knowing that events are accurately portrayed, as well as having good time- and date- stamps from the devices that produce the materials, will go a long way toward creating a body of materials that will support human rights work for the long-term.

New Library Structure Blends Digital and Traditional Research

Today’s post isn’t about human rights per se, but it does focus on our interest on digital resources and highlights an interesting new approach to large research collections. That said, the University of Chicago collections house a number of important works related to human rights, and the system described below may make them broadly accessible within and beyond the quads. –Sarah

Image coutresy of http://www.wired.com/underwire

Next week, the University of Chicago Libraries will open the new Joe and Rika Mansueto library. As described in this Wired article, the very structure of the new library is designed to capitalize on the new realities of digital research in order to facilitate research in the libraries important physical collections. As students and young faculty increasingly start the research process on-line rather than in the stacks, use of library space is fundamentally shifting. The Mansueto library recognizes and harnesses this shift by creating an on-line research space that directs investigators to physical resources now stored in a 50 foot deep underground vault that will house 3.5 million volumes of work not otherwise available in a digital medium. Once investigators determine that they need to consult a physical resource to complement what they’ve found digitally, they can digitally request that resources. These digital requests can be made from anywhere in the world via the on-line catalog or email. Once the request is received, the library’s automated system retrieves the item from the vault within five minutes and places it on hold for seven days. At this point, of course, the researcher will have to physically collect the book from the library. The major innovation of this system is that it allows people to digitally search key resources that are only available physically. The hope is that appropriating digital research practices to direct work back to physical collections will maintain the relevance of these collections by increasing the range of resources that increasingly digitally-oriented students consult in their research.

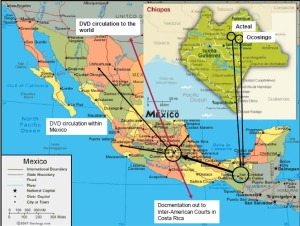

Preliminary Results for the CRL Human Rights Electronic Evidence Study

At long last, preliminary results for the Human Rights Electronic Evidence Study at the Center for Research Libraries are available. Please see the report “Human Rights Electronic Evidence Study: Interim Report” (also available at CRL’s webpage ) for a detailed discussion of how documentation becomes digitized and formalized as it moves through local networks of human rights organizations. The report focuses on field observations from Chiapas, Mexico and Kigali, Rwanda, but we believe that the results may be generalizable to most local situations. Our main finding: small organizations tend to document human rights violations either orally or with paper documentation, but then, as they work with larger organizations with more digital resources, the documentation is converted to digital formats. Of course at all levels, what gets documented in the first place is determined by local needs and goals, so there is no real standard practice for documentation within these networks of organizations.

Coming soon: a summary of digital documentation practices for human rights organizations in Moscow and Saint Petersburg.

Google & Twitter Use Land Lines to Help Egyptians Tweet

As posted at, NEWS 3.o MEDIA: LAB, on February 1, 2011, digital social media needs to sometimes fall back on traditional technology–in this case the telephone land line–to get messages out. As the quoted post below illustrates, Google’s newly acquired SayNow technology allowed the group to work with Twitter to build a work-around for the Egyptian government’s shut down of internet systems in the face of anti-government protests.

Speak-2-Tweet – Google, Twitter and SayNow enable Egyptians to be heard

A group of engineers from Google, Twitter and SayNow (which Google acquired last week) were hard at work building a speak-to-tweet service for protesters in Egypt this weekend.

The service, which is already live, enables users to send tweets using a voice connection.

Google Blog :: It’s already live and anyone can tweet by simply leaving a voicemail on one of these international phone numbers (+16504194196 or +390662207294 or +97316199855) and the service will instantly tweet the message using the hashtag #egypt. No Internet connection is required. People can listen to the messages by dialing the same phone numbers or going to twitter.com/speak2tweet.

Admissability of Digital Data in the Court Room Outside of the US

Over the summer months of 2010, The Documentalist presented a five part series on the admissibility of electronic documentation as evidence in the American court system titled “Legal Considerations for Electronic Evidence.” These five posts focused on a variety of issues, starting with an overview of the admissibility of electronic evidence in the U.S. and moving through Relevance and Authenticity, Applying Rules of Authenticity, Hearsay, and finally Original vs. Duplicate Documents and Unfair Prejudice. Though these posts aren’t comprehensive by any means, they do cover the major issues of rules of evidence and legal precedent that apply to determining whether and how electronic documents can serve as evidence in legal cases before the court–an important topic in the field of human rights documentation, especially as certain sectors of human rights work move to a greater use of and dependence upon digital documentation in activism. Fortunately, in coping with electronic evidence, American legal practice has been able to extend and apply the Federal Rules of Evidence to accommodate the many issues inherent to electronic evidence. The trick has been to draw a direct line of descent (so to speak) from physical documentation to digital forms in order to establish precedent for applying the rules of evidence to electronic media.

Over the summer months of 2010, The Documentalist presented a five part series on the admissibility of electronic documentation as evidence in the American court system titled “Legal Considerations for Electronic Evidence.” These five posts focused on a variety of issues, starting with an overview of the admissibility of electronic evidence in the U.S. and moving through Relevance and Authenticity, Applying Rules of Authenticity, Hearsay, and finally Original vs. Duplicate Documents and Unfair Prejudice. Though these posts aren’t comprehensive by any means, they do cover the major issues of rules of evidence and legal precedent that apply to determining whether and how electronic documents can serve as evidence in legal cases before the court–an important topic in the field of human rights documentation, especially as certain sectors of human rights work move to a greater use of and dependence upon digital documentation in activism. Fortunately, in coping with electronic evidence, American legal practice has been able to extend and apply the Federal Rules of Evidence to accommodate the many issues inherent to electronic evidence. The trick has been to draw a direct line of descent (so to speak) from physical documentation to digital forms in order to establish precedent for applying the rules of evidence to electronic media.

However, a question emerges when we begin to look at the admissibility of electronic documents in court systems outside of the U.S. that do not have a long-established set of Rules of Evidence and precedent for applying them. Each court system must therefore establish its own practices for processing and presenting electronic evidence, and in doing so, at least some of the world’s legal systems are drawing on U.S. legal practice and precedent as a basis for establishing their own body of precedent vis-a-vis electronic evidence in court cases–a point that the article from Bangladesh summarized below makes clearly.

Dealing with Electronic Evidence Outside of the U.S.

In the article “Admissibility of Surveillance Evidence: A Legal Perspective,” (ASA University Review, 2 (2):1-30. 2008) author Abu Hena Mostofa Kamal raises important questions about legal rights to privacy internationally in the face of a rapidly growing world of digital surveillance technology and whether or how these new sources of digital data can be submitted as evidence in court. Given the nature of the Human Rights Electronic Evidence Study, the latter question is of greater interest here. But most interestingly, Mr. Kamal is writing from Bangladesh in a journal that focuses on Bangladeshi scholarship–particularly socio-economic research–for a young university (founded in 2006) dedicated to providing quality education to the lower income strata of Bangladesh (see ASA University Bangladesh).

As Mr. Kamal points out, the first step that courts must take vis-a-vis surveillance evidence is to determine whether they were legally collected and did not infringe on a defendant’s rights to privacy. He notes that this question is approached differently in three court systems: The U.S., the U.K., and Australia. Specifically, in the U.S. and Australia, protection of rights to privacy can cause courts to throw out otherwise damning evidence, thus allowing criminals to escape conviction of crimes, while in the U.K., surveillance data might be deemed to be illegally gained, but allowed into court if the severity of the alleged crime under consideration is deemed high enough by the justice that he will override personal rights in favor of public safety and successful prosecution of major crimes (Kamal, 2008:10-12). Judicial discretion in such cases raises many questiosn vis-a-vis personal rights vs. the rights of the state to prosecute criminal behavior and the rights of citizens to be protected from the same.

Once the question of the legality of electronically generated surveillance evidence has been established, the same needs to be proven to be admissible as evidence. In explaining this process, Mr. Kamal (writing in Bangladesh for a Bangladeshi audience) draws heavily upon American legal practice and precedent. The main problem he sees for establishing the admissibility of electronic surveillance data is a deep distrust of its reliability and authenticity:

Courts always challenge the admissibility of evidence procured from surveillance and interception gadgets on the basis of the following grounds:

[a] Surveillance techniques are untrustworthy as there remain chances of manipulation. A manupulated datum or photograph or infromation is not admissible as evidence (Kamal, 2008:7).

Mr. Kamal counters, however, that if we consider surveillance data as yet another form of electronically created documentation similar to digital photos, emails, or computer generated documents, then courts can call on U.S. standards of relevance, authenticity, and reliability to determine whether these materials can serve as evidence in court cases. In drawing this parallel between surveillance evidence and any other form of electronically created documentation, Mr. Kamal argues that surveillance data is subject to the same risks of tampering as any other form or electronic evidence and therefore is subject to the same standard of evidence as any other electronic form (compare the following with discussions at The Documentalist of Relevance and Authenticity, Applying Rules of Authenticity, and Original vs. Duplicate Documents and Unfair Prejudice):

The standards that are essential for determining the admissibility of digital evidence derived from surveillance gadgets are as follows:

1. Relevance: Courts admits [sic] only relevant evidence. So, evidence must be logically cnnected to the dispute and have probative value.

2. Authenticity: Once evidence is found to be relevant, it must be authenticated. It means there must be a guranatee of trustworthiness attached to the evidence. Authentication standards are meant ‘to ensure that the evidence is what it purports to be, and how rigorous a foundation is needed to make this finding depends on the existence of something that can be tested in order to prove a relationship between teh evidence and an individual and control against the perpetration of fraud.’

3. Reliability: Another evidentiary lynchpin is that evidence must be original. This rule is known as the ‘Best Evidence Rule’. As per American law, an ‘original’ of a writing or recording is the writing or recording itself or any counterpart intended to have the same effect by a person executing or issuing it. IF data are stored in a computer or similar device, any printout or other output readable by sight, shown to reflect the data accurately, is an original” (Kamal, 2008:8).

When considering these points, Mr. Kamal further observes (also following American legal practice) that relevance, authenticity, and reliability are ultimately to be supported by expert witness testimony attesting to processes employed in creating originals, whether not not originals have been tampered with, and the accuracy of copies in determining if they can stand in for originals as evidence in court cases.

Mr. Kamal makes the above case for treating surveillance data as any other form of electronically created documentation drawing from primary and secondary sources related the the U.S. Federal Rules of Evidence. He then summarizes a number of U.S. court cases that establish precedent for treating surveillance as we would electronic evidence in general. In so doing, he sets up U.S. legal practice and precedent as a model for international courts when determining the admissibility of such evidence (provided it was legally obtained) in criminal court cases.

New Resource at CRL: Topic Guide in Human Rights

Image courtesy of http://www.crl.edu

Happy New Year to you all. The Documentalist has been on a bit of a hiatus with the winter holidays, but here we are in a new year and what better way to kick it off than to introduce a newly launched resource at the Center for Research Libraries-Global Resources Network (CRL-GRN) designed to support research in human rights: The Topic Guide in Human Rights. As you can see in the above image, the topic guide exists at the CRL-GRN Website and points to a number of useful sources accessed through the pink topic tabs pictured. The “Landscape” provides an overview to the issues confronting human rights documentation and archiving endeavors (you will also find a link to our Human Rights Electronic Evidence Study under this tab), while the “CRL Collections” tab takes users to a sample of the variety of holdings CRL maintains related to human rights. Finally, the “Related Resources” tab presents a number of on-line resources related specifically to archiving digitally produced materials in human rights–a topic of on-going research here at CRL. There are also a variety of other links to explore within the topic guide, so please visit and learn more about what CRL has to offer in the area of human rights.

leave a comment