Admissability of Digital Data in the Court Room Outside of the US

Over the summer months of 2010, The Documentalist presented a five part series on the admissibility of electronic documentation as evidence in the American court system titled “Legal Considerations for Electronic Evidence.” These five posts focused on a variety of issues, starting with an overview of the admissibility of electronic evidence in the U.S. and moving through Relevance and Authenticity, Applying Rules of Authenticity, Hearsay, and finally Original vs. Duplicate Documents and Unfair Prejudice. Though these posts aren’t comprehensive by any means, they do cover the major issues of rules of evidence and legal precedent that apply to determining whether and how electronic documents can serve as evidence in legal cases before the court–an important topic in the field of human rights documentation, especially as certain sectors of human rights work move to a greater use of and dependence upon digital documentation in activism. Fortunately, in coping with electronic evidence, American legal practice has been able to extend and apply the Federal Rules of Evidence to accommodate the many issues inherent to electronic evidence. The trick has been to draw a direct line of descent (so to speak) from physical documentation to digital forms in order to establish precedent for applying the rules of evidence to electronic media.

Over the summer months of 2010, The Documentalist presented a five part series on the admissibility of electronic documentation as evidence in the American court system titled “Legal Considerations for Electronic Evidence.” These five posts focused on a variety of issues, starting with an overview of the admissibility of electronic evidence in the U.S. and moving through Relevance and Authenticity, Applying Rules of Authenticity, Hearsay, and finally Original vs. Duplicate Documents and Unfair Prejudice. Though these posts aren’t comprehensive by any means, they do cover the major issues of rules of evidence and legal precedent that apply to determining whether and how electronic documents can serve as evidence in legal cases before the court–an important topic in the field of human rights documentation, especially as certain sectors of human rights work move to a greater use of and dependence upon digital documentation in activism. Fortunately, in coping with electronic evidence, American legal practice has been able to extend and apply the Federal Rules of Evidence to accommodate the many issues inherent to electronic evidence. The trick has been to draw a direct line of descent (so to speak) from physical documentation to digital forms in order to establish precedent for applying the rules of evidence to electronic media.

However, a question emerges when we begin to look at the admissibility of electronic documents in court systems outside of the U.S. that do not have a long-established set of Rules of Evidence and precedent for applying them. Each court system must therefore establish its own practices for processing and presenting electronic evidence, and in doing so, at least some of the world’s legal systems are drawing on U.S. legal practice and precedent as a basis for establishing their own body of precedent vis-a-vis electronic evidence in court cases–a point that the article from Bangladesh summarized below makes clearly.

Dealing with Electronic Evidence Outside of the U.S.

In the article “Admissibility of Surveillance Evidence: A Legal Perspective,” (ASA University Review, 2 (2):1-30. 2008) author Abu Hena Mostofa Kamal raises important questions about legal rights to privacy internationally in the face of a rapidly growing world of digital surveillance technology and whether or how these new sources of digital data can be submitted as evidence in court. Given the nature of the Human Rights Electronic Evidence Study, the latter question is of greater interest here. But most interestingly, Mr. Kamal is writing from Bangladesh in a journal that focuses on Bangladeshi scholarship–particularly socio-economic research–for a young university (founded in 2006) dedicated to providing quality education to the lower income strata of Bangladesh (see ASA University Bangladesh).

As Mr. Kamal points out, the first step that courts must take vis-a-vis surveillance evidence is to determine whether they were legally collected and did not infringe on a defendant’s rights to privacy. He notes that this question is approached differently in three court systems: The U.S., the U.K., and Australia. Specifically, in the U.S. and Australia, protection of rights to privacy can cause courts to throw out otherwise damning evidence, thus allowing criminals to escape conviction of crimes, while in the U.K., surveillance data might be deemed to be illegally gained, but allowed into court if the severity of the alleged crime under consideration is deemed high enough by the justice that he will override personal rights in favor of public safety and successful prosecution of major crimes (Kamal, 2008:10-12). Judicial discretion in such cases raises many questiosn vis-a-vis personal rights vs. the rights of the state to prosecute criminal behavior and the rights of citizens to be protected from the same.

Once the question of the legality of electronically generated surveillance evidence has been established, the same needs to be proven to be admissible as evidence. In explaining this process, Mr. Kamal (writing in Bangladesh for a Bangladeshi audience) draws heavily upon American legal practice and precedent. The main problem he sees for establishing the admissibility of electronic surveillance data is a deep distrust of its reliability and authenticity:

Courts always challenge the admissibility of evidence procured from surveillance and interception gadgets on the basis of the following grounds:

[a] Surveillance techniques are untrustworthy as there remain chances of manipulation. A manupulated datum or photograph or infromation is not admissible as evidence (Kamal, 2008:7).

Mr. Kamal counters, however, that if we consider surveillance data as yet another form of electronically created documentation similar to digital photos, emails, or computer generated documents, then courts can call on U.S. standards of relevance, authenticity, and reliability to determine whether these materials can serve as evidence in court cases. In drawing this parallel between surveillance evidence and any other form of electronically created documentation, Mr. Kamal argues that surveillance data is subject to the same risks of tampering as any other form or electronic evidence and therefore is subject to the same standard of evidence as any other electronic form (compare the following with discussions at The Documentalist of Relevance and Authenticity, Applying Rules of Authenticity, and Original vs. Duplicate Documents and Unfair Prejudice):

The standards that are essential for determining the admissibility of digital evidence derived from surveillance gadgets are as follows:

1. Relevance: Courts admits [sic] only relevant evidence. So, evidence must be logically cnnected to the dispute and have probative value.

2. Authenticity: Once evidence is found to be relevant, it must be authenticated. It means there must be a guranatee of trustworthiness attached to the evidence. Authentication standards are meant ‘to ensure that the evidence is what it purports to be, and how rigorous a foundation is needed to make this finding depends on the existence of something that can be tested in order to prove a relationship between teh evidence and an individual and control against the perpetration of fraud.’

3. Reliability: Another evidentiary lynchpin is that evidence must be original. This rule is known as the ‘Best Evidence Rule’. As per American law, an ‘original’ of a writing or recording is the writing or recording itself or any counterpart intended to have the same effect by a person executing or issuing it. IF data are stored in a computer or similar device, any printout or other output readable by sight, shown to reflect the data accurately, is an original” (Kamal, 2008:8).

When considering these points, Mr. Kamal further observes (also following American legal practice) that relevance, authenticity, and reliability are ultimately to be supported by expert witness testimony attesting to processes employed in creating originals, whether not not originals have been tampered with, and the accuracy of copies in determining if they can stand in for originals as evidence in court cases.

Mr. Kamal makes the above case for treating surveillance data as any other form of electronically created documentation drawing from primary and secondary sources related the the U.S. Federal Rules of Evidence. He then summarizes a number of U.S. court cases that establish precedent for treating surveillance as we would electronic evidence in general. In so doing, he sets up U.S. legal practice and precedent as a model for international courts when determining the admissibility of such evidence (provided it was legally obtained) in criminal court cases.

HURIDOCS & IHRDA Collaborate on Caselaw Analyzer

HURIDOCS has been working with the Institute for Human Rights and Development in Africa (IHRDA) to develop a on-line tool called the Caselaw Analyzer, which will allow IHRDA (and other groups in the future) to “easily browse inter-related court decisions, to quickly access the primary caselaw for a given type of [human rights] violation, to highlight and comment relevant sections of a decision, and to share their commentary with their colleagues and work collaboratively on case research” (see the full description of the program and project here). The goal of the project was to help IHRDA have quick access to both the body of court decisions the organization has collected from the African Commission for Human and People’s Rights (ACHPR), and to provide a means of quickly and efficiently accessing caselaw research lawyers have already done in order to apply that research to new cases that the organization takes on. You can access IHRDA’s Caselaw Analyzer connection here. As stated in HURIDOCS’ description of the program, there is a particular challenge associated with using and managing caselaw that this new program will help organizations like IHRDA address:

Court decisions often reference specific paragraphs of other decisions, which in turn reference other decisions. Caselaw Analyser allows you to easily navigate from one decision to the next. And because it uses inline-browsing to jump stright to the quoted paragraph, you don’t even lose your page. Also, all incoming and outgoing citations are listed next to the text of the decision.

Also, CaseLaw Analyser will use a specifically designed CaseRank algorythm, meaning that the decisions that are the most often referenced, will appear first (like Google’s PageRank). This gives the user an indication of which cases are the most important: the primary caselaw.

In addition to assisting in the organization and management of such data, in the future, the program will also offer a social networking and collaboration feature that will allow multiple individuals within an organization to develop a case together on-line. This feature will permit organization members working over a broad geographic area to consolidate notes, caselaw, and opinions as they develop new cases.

Facebook and Digital Activism

As part of my work on the Human Rights Electronic Evidence Study here at CRL, I spend a certain portion of my days searching the Web for instances and examples of how people use social media to organize activism. Over the last couple of weeks, I have run across a couple of pieces about using Facebook in human rights. One looks at ways of informing the public of human ribelow.

–Sarah

How Facebook got involved in human rights film

By Alex Ben Block – Thu Sep 9, 6:18 am ET on Yahoo! News

Image courtesy of http://www.facebook.com

Though the article “How Facebook got involved in human rights film” does not provide a useful link to actual human rights content on Facebook, it does describe the work of Michealene Cristini Risley, a documentary film maker who traveled to Zimbabwe in 2007 “to make a documentary exposing sexual abuse by men who believed raping virgin girls would cure their HIV/AIDS”. Early in her trip, Ms. Risley was arrested and detained–see the article for more details on her experiences–and perhaps one of the most striking features of her detainment was the central role that Facebook played in her release:

After three days, an American journalist who read about Risley’s predicament on her Facebook page alerted a CIA agent, who made a call to Zimbabwe president Robert Mugabe. She was released unharmed and fled the country with her HD footage.

Upon returning to the US, Ms. Risley followed through on making her film in defense of women and girls in Zimbabwe–“Tapestries of Hope.” The film is launching on September 28, 2010 with extensive support from social media, not least, Facebook:

On September 28, Risley will be at Facebook headquarters in Palo Alto, Calif., to thank its employees for the company’s role in her release and to go on Facebook’s LIVE streaming video channel to share her story and answer questions. It’s all part of the coordinated launch of the documentary, “Tapestries of Hope,” that came out of her trip.

Her Facebook appearance, which will be available for replay after the initial airing, serves as the centerpiece of an innovative marketing and promotional strategy employing new media — especially social media — as well as a limited theatrical release, cable TV and in-theater ads and hundreds of house parties, all to raise awareness of the issue and encourage Congress to pass the International Violence Against Women Act, now winding its way through the U.S. Senate.

You can find information on the film release at the Tapestries of Hope Facebook page. According to the article reviewed here, Ms. Risley’s Facebook appearance will be released on Facebook after the initial launch of the film on September 28th.

Hard to find human rights information on Facebook, but it’s there

Unfortunately, finding out about Facebook initiatives such as the “Tapestries of Hope” project is quite challenging. There is no clear organization of human rights information on Facebook–users need to know what they’re looking for, which they likely learn through their extended on-line social network connections. For the time being, Facebook users generally interested in Human Rights issues addressed through the site can do a general search for “human rights”–the search pulls up a number of hits, but it’s not an elegant tool. Hopefully, if Facebook is serious about lending itself as a powerful tool for activism and awareness, it will devise a better means of leading users to dedicated human rights spaces. In the meantime, we have to content ourselves with imperfect and imprecise search mechanisms within the site.

A DigiActive Introduction to facebook Activism

I found this resource through an informative post at the media/anthropology blog created by John Postill. On September 12, 2010, Mr. Postill wrote a piece called “Facebook activism out of Burma, Morocco, and Egypt” that–in addition to providing notes on “A DigiActive Introduction to facebook Activism”–provides summaries of three human rights efforts that use facebook as an informative mobilizing tool. Regarding the strengths and weaknesses of facebook as an activism tool, Mr. Postill’s notes on the report indicate:

I found this resource through an informative post at the media/anthropology blog created by John Postill. On September 12, 2010, Mr. Postill wrote a piece called “Facebook activism out of Burma, Morocco, and Egypt” that–in addition to providing notes on “A DigiActive Introduction to facebook Activism”–provides summaries of three human rights efforts that use facebook as an informative mobilizing tool. Regarding the strengths and weaknesses of facebook as an activism tool, Mr. Postill’s notes on the report indicate:

“The social basis of activism explains why Facebook, an increasingly popular social networking site, is a natural companion for tech-savvy organizers. Because of the site’s massive user base and its free tools, Facebook is almost too attractive to pass up. However, the site has its flaws and is not a guarantee of organizing success. This guide is written to provide some insights into what works, what doesn’t work, and how best to use Facebook to advance your movement.”

[…]

Pros: How Facebook Can Help Activists

- Lots of People Use Facebook

- The Price is Right

- Hassle-Free Multimedia

- Opt-in Targeting

[…]

Cons: Why Facebook Isn’t a Silver Bullet

- Content on the Site is Disorganized

- Dedication Levels are Opaque

- Facebook isn’t Designed for Activism

(Source: John Postill)

Satellite Image Archives

The last couple of posts have dealt with the technology of satellite imagery and how this imagery can serve human rights. However, of more interest to some might be the archiving of satellite images. After all, the benefit of satellite imagery for human rights work is predicated on access to “before” and “after” images that illustrate physical destruction of villages or farms in the wake of human rights atrocities–the before images perforce come from past images that organizations acquire from archives of stored and cataloged materials collected by various geo-spatial imaging companies’ satellites.

Because satellite imaging companies are for-profit, information about their archiving practices is fairly limited, but some information is available on-line and is summarized below for three large imaging firms: GeoEye, ImageSat International, and Digital Globe. These companies have each provided images to human rights organizations or to researchers investigating human rights events, either as donations or through purchase arrangements.

GeoEye

GeoEye maintains an archive of satellite images and a suite of services for accessing them. These services are available through their GeoFUSE program, described as follows:

GeoEye’s Imagery Sources collect vast amounts of high-resolution satellite and aerial imagery from around the globe each day. This imagery is processed and used in a multitude of applications such as mapping, disaster response, infrastructure management, and environmental monitoring. Now, with GeoEye’s new suite of Search & Discovery tools, our customers can browse the GeoEye image catalog archives, quickly and easily locating and previewing imagery for their specific needs. Using the information obtained through use of these tools, our customers can easily communicate the information necessary to place orders for imagery products that meet their project requirements.

Access services include: Online Maps, Google Earth Tools, Online Resource Center, Advanced Search Options, Toolbar for ArcMaps (a desk top GIS application), Help & Documentaiton, and Image search (Resourcesat-1 catalogs). Some preliminary searching can be done through these tools at the website and selected preview images can be stored in a personal file at the GeoEye Webpage for reference and purchase. GeoEye also offers imagery for free to academics, human rights organizations, and other non-profits through the GeoEye Foundation.

ImageSat International.

ImageSat has an archive, but little information about it is available online. The Website states:

ImageSat maintains an imagery archive, which contains all imaged EROS A data, including that which is down-linked by the ground control stations in ImageSat’s Global Network. Customers may purchase this imagery at preferred prices. To enquire about purchasing imagery from the ImageSat Imagery Archive, contact our Order Desk or call us at +972-3-7960627.

There are sample images available through the gallery, but there does not appear to be a means of searching preview images as there is at GeoEye’s website. The page requests that you call for information.

Digital Globe

Digital Globe also maintains an archive of their satellite imagery, which you can learn more about by contacting them directly at the following:

Please Contact Customer Service for information on searching The DigitalGlobe™ Archive

E-mail: info@digitalglobe.com

Toll Free: 800.496.1225 or

Phone: 303.684.4561

Fax: 303.684.4562

Currently, Digital Globe is offering free imagery for coverage of the Haiti crisis, which is available on their gallery page. Click on the “Free Access to Haiti Imagery” button and you will be taken to an order form for imagery requests. They also offer an on-line image search feature that allows site visitors to sample the imagery in the archive according to region of the world. An interactive map leads visitors through the preview process. Standard imagery is available upon request:

Standard Imagery can be acquired directly from the DigitalGlobe archive or you can submit a new collection request. Standard Imagery is ordered by area, with a minimum purchase of 25 km2 (~10 mi2) for archive orders. For tasking, the minimum area for ordering is 25 km2 (~10 mi2), but minimum pricing rules apply, depending on the tasking level selected. If your order crosses more than one strip, one standard imagery product per scene is delivered.

Products are delivered on your choice of standard digital media with Image Support Data files including image metadata.

MobileActive: Supporting Social Action Through Mobile Technology

MobileActive is an organization that seeks to bring together research and user experiences of mobile technology to support social action. As observed on their “about” page:

Mobile phones are proliferating at astounding rates across socio-economic and cultural boundaries, revolutionizing the way we organize ourselves.

With more than 4.5 billion mobile subscriptions in circulation in 2009, they are found in every corner of the world, used by people to communicate with each other, and access and deliver information and services. These trends are highly promising for NGOs and civil society organizations that can now engage people on issues that matter most — through always-on, always-on-hand devices.

MobileActive.org’s vision is to help organizations make use of the most ubiquitous communications technology in the world with data, tools, and how-to resources; build a network of practitioners and technologists in a supportive community of practice; and highlight and explore the many innovative campaigns and projects — their lessons learned.

The website contains a blog that updates information on a variety of projects, research resources (including an annotated bibliography of print and web resources), and a comprehensive search function. Many of the issues they cover relate to human rights in its many guises–economic rights, crisis prevention or response, gender rights, environment, etc. The group also support Citizen Media through mobile devises.

MediaActive has video presence on the web through Vimeo–site that has a number of social impact videos in general–well worth a search to see what they have. MobileActive has published two videos to date–both available here.

GLIFOS-Media: Rich Media Archiving

Rich-media preservation

As posted on November 4, 2009, The University of Texas Libraries Human Rights Documentation Initiative (HRDI) has been working with the Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre in Rwanda on a pilot digital archiving program that takes advantage of a rich media platform called GLIFOS media. GLIFOS provides a social media tool kit that was originally created to meet the needs of a distance learning program at the Universidad de Francisco Marroqín in Guatemala, but it proves to also be promising as a tool for human rights archiving (see the article “Non-custodial archiving: U Texas and Kigali Memorial Center” at WITNESS Media Archive). As a rich-media wiki, GLIFOS is designed to integrate digital video, audio, text, and image documents through a process that “automates the production, cataloguing, digital preservation, access, and delivery of rich-media over diverse data transport platforms and presentation devices.” GLIFOS media accomplishes this by presenting related documents–for example, video of a lecture, a transcript of the same, and associated PowerPoint slides–in a synchronized fashion such that when a user highlights a particular segment of a transcript, for example, the program locates and plays the corresponding segment of the video and also locates the related Power Point slide. This ability to seamlessly synchronize and present related digital media translates well to the human rights context by allowing for the cataloging and integration of video material, documents containing testimonies, photographs, and transcripts. Materials that all relate to a single event can be pulled together and presented in a holistic fashion, which is useful for activism and scholarship.

GML: The Key to Preservation

In order to support the presentation of this integrated information for users, GLIFOS needed to ensure that materials can be read and accessed across existing digital presentation platforms (e.g., web browsers, DVDs, CD) and readers (e.g., PCs or PDAs), as well as on platforms yet-to-be-created (see “XML Saves the Day,” an article written by the developers in 2005 for more detail). This was accomplished by indexing and annotating all digital documents stored in the GLIFOS repository with an XML-based language called the “GLIFOS Markup Language,” or GML. The claim is that “GML is technology, platform, and format independent” (Ibid), thus allowing for preservation of established relationships between materials. Basically, the GML language allows users of GLIFOS to create a metafile that determines the relationships between related multi-media records held in a repository in such a way that the relationships between files are maintained across a variety of media reading platforms. This is possible because GML is a significantly stripped-down markup language that requires little or no translation from one reader to the next, thus content is preserved as technology changes and evolves.

GLIFOS and Human Rights Documentation

Given that GLIFOS is designed to catalog, index, and synchronize a wide variety of digital media types, it proves to be a promising tool for aiding in digital archiving. The GLIFOS GML protocol allows the program to access and present cataloged materials through the meta-relationships it establishes for records; and because GML is a streamlined markup language that allows multiple platforms to present and read digital documents, these relationships have been successfully maintained when migrated to entirely new data reading and presentation platforms. As long as the repository of documents that GLIFOS accesses remains intact, both in terms of the materials stored there and their associated metadata, and as long as new media platforms continue to read older video and image media files, use of the GLIFOS Markup Language aids in preservation by providing a means of cataloging and indexing documents using GML, as well as preserving the synchronized links and interactions that GLIFOS establishes between related documents over time.

[1] See http://www.glifos.com/wiki/images/f/f5/Arias_reichenbach_pasch_mLearn2005.pdf

An Attempt at Web-Archiving Human Rights in Eritrea

I found the Web page that I review below in a comment on the WITNESS Media Archive blog. It struck me as an interesting example of a local attempt to gather together human rights documentation, as well as a bit of a cautionary tale–much of the information in the site comes from links to other Web resources that have subsequently disappeared.

–Sarah

EHREA: Eritrean Human Rights Electronic Archive

Flag Map of Etriea. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.org

EHREA, or the Eritrean Human Rights Electronic Archive, represents an effort to consolidate information about human rights abuses that have taken place in Eritrea since independence from Ethiopia in 1991. The goal of the site is to archive photos, testimonies, media reports, video clips, and links to related Web sites in an effort to “increase public awareness of injustices carried out in Eritrea and elsewhere by the PFDJ [People’s Front for Democracy and Justice] and to serve as a platform to hasten the introduction of justice and democracy in Eritrea.” People are invited to submit any information or documentation they have concerning abuses to a personal email address for the individual who appears to be responsible for the Web page.

The website is a bit difficult to navigate–It isn’t clear how materials are preserved and the organization is a bit piece-meal–but it’s worth exploring because of the variety of information and resources available. Equally interesting is the number of links to resources that are broken, highlighting the fragile nature of human rights Web sites, especially in states or areas that have fewer Web resources than we do in the West. It appears that the organizer of this Web site has been able to capture images of Web pages, but they no longer link when the pages are shut down for whatever reason.

Masking on-line activity to protect human rights workers

One of our goals with this blog is to provide information about various services and technologies we encounter that might interest human rights activists, scholars, or archivists. If you have suggestions for products or services you think we should review, please let me know!

–Sarah

Tor Anonymity Online

Interlocking layers of information. Image courtesy of johnpowers.us

As the world increasingly shifts to the Web for communicating, there seems to be an equal increase in the need of repressive governments, corporations, and agencies to read over people’s shoulders (so to speak), by monitoring the flow of communication and information across the Web. This is worrisome in general, but is particularly problematic for human rights work. Activists, whistle-blowers, witnesses, and victims want to share what they know, but they have to be careful of using the Web because repressive regimes have gotten quite good at intercepting emails, blogs, and other electronic forms of communication and using them to identify the physical locations and identities of senders and the recipients. They then use the information to detain people, or even as an excuse to torture or execute them. Recent events in Iran and China are perfect examples of how governments monitor and censor internet communications with the intent to quash popular movements by committing violence against those who try to stand up to repressive policies and practices.

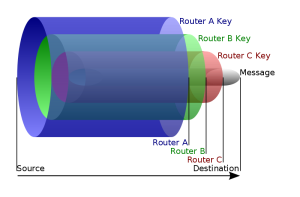

One popular resource for circumventing Web censorship is a free program called Tor–an acronym for “The onion router.” Onion routing differs from traditional communication on the Web in that it sends encrypted messages along a roundabout path rather than zipping them straight from point A to point B. Typically, when a user uses their internet browser or email program, messages move directly from sender to recipient across a single, proprietary server (e.g. Yahoo!, Gmail, Hotmail, etc.). This may be an incredibly efficient means of moving information, but a lot of identifying information is visible to third parties that lurk on these servers—your IP address provides precise information about where you are physically located when you send a given message, and the delivery header that is attached to a message to make sure that it gets to the recipient contains information about the content of the message itself that is easily read by outside parties. (This, by the way, is what allows Gmail to customize advertisements within their email program—they can scan the content of headers for messages you send and receive, looing for key words that trigger classes of ads).

An onion router is a program that masks your message from outside view by hiding it in a layered data bundle called an “onion.” The onion shuttles the hidden message through a randomly selected series of proxy servers, making it much more difficult for anyone monitoring net activity to identify sender, receiver, or the content of the message. There are several programs that provide this service for a fee, but in Tor’s case, the service is free because the proxy network consists of members who voluntarily make their PCs available as network nodes, or “onion routers.” Information about the Tor Project (as the program is formally called) is available at www.torproject.org, where you can download free software that allows you to send and receive messages anonymously. There are no limitations on who can use the service, and users aren’t required to volunteer their own PCs to the network, but they are strongly encourage to.

What is Onion Routing?

Imagine standing in a large, crowded room and you are handed a brown paper cylinder with your name on it. The person who hands it to you tells you to peel the paper with your name on it off of the cylinder to expose a new layer with a new name on it–your task is to deliver the cylinder to the person named, tell her to peel that layer of paper off and pass it on to the next person named and tell him to do the same. This goes on until the very center of the cylinder is handed off to the person to whom it is addressed. The idea is that the center of the cylinder contains a message sent to the final recipient by the very first person to hand the cylinder off. But, because the cylinder traveled through so many hands, and along a random path through the crowd, anyone observing the receipt of the final message (or any of the hand-offs at any point along the way, for that matter) has no idea where it came from originally; he or she only saw the final hand-off in a relay of hand-offs.

Onion routing diagram courtesy of wikipedia.org/wiki/onion_routing

The situation described above is a good analogy for onion routing. When a user logs into Tor using the modified version of the FireFox Web browser provided at the Tor Web page, the program automatically scans the network of member PCs to identify which ones are available for data receipt and transfer. The program then writes a series of layered encryption codes that will route the sender’s message through a randomly selected subset of those PCs. When each PC in the selected series receives the bundle, it reads the layer of code addressed to it, which will instruct the PC to re-encrypt the message bundle and send it to the next PC in the series, which, in turn will read and execute its layer of coded instructions, and so on until the message reaches its destination. Third parties observing the net as the message moves through this roundabout path can see that information is moving, but they only see the activity between one PC and the next—they don’t see the complete path and so cannot easily identify the origin and destination for the message. Furthermore, because the message is wrapped in layers of encryption, it cannot be read while in-transit. And, because the message bundle is re-encrypted every step of the way, an bserver will see one unreadable message arriving to a PC and what looks like a different unreadable message going out to the next PC in the chain. Thus, Tor offers an effective alternative to such visibility by hiding this information, but the trade off is that delivery is slow and cumbersome.(For more detailed information about how this process functions, see the onion routing article at Wikipedia or the overview page at Tor.)

Book Review: Video For Change

Book image courtesy of WITNESS.org

Title: Video for Change: A Guide for Advocacy and Activism

Editors: Sam Gregory, Gillian Caldwell, Ronit Avni, and Thomas Harding (with a forward by Peter Gabriel)

Publication information: Ann Arbor, Michigan: Pluto Press. © 2005.

To Purchase: See The WITNESS Store

Review

Video for Change is produced by the human rights organization WITNESS (their motto is “See it. Film it. Change it.”), and consists of 7 practical papers for how everyday people can easily and professionally incorporate video cameras into activism. The basic message? You don’t have to go be a professional film maker to make effective films with professional polish. The book’s goal is to get cameras into the hands of advocates and get them recording as quickly as possible so that important human rights material gets recorded, disseminated, and saved.

Topics covered include:

- The power of video in advocacy and how to plan for its most effective use

- Safety issues ranging from protecting your own safety as an advocate to protecting the safety of those you record, as well as issues related to informed consent and the legal use of videos once they are created.

- Strategies for using video as a storytelling medium, including advice on planning the structure of a final video to make the most impact within a well-planned narrative.

- Straightforward technical advice on equipment and video techniques that will allow everyday people with no formal training in film-making to quickly begin using video in their field work.

- Editing advice aimed at helping advocates to keep their target audiences in mind as they compile their final documentary product.

- video as legal evidence–advice on how to ensure that the videos that advocates produce can be admitted to a court of law, including guidelines for collecting appropriate metadata and provenance.

Each chapter draws on case studies to illustrate the efficacy of video in human rights work and provides diagrams, photographs, charts, and other visual aids to present straightforward steps for moving through the entire process of video advocacy: from recording the raw footage to producing and disseminating the final edited product. At the end of the book, there are a number of appendices providing model recording and production plans, templates for consent and release forms, and production checklists.

1 comment